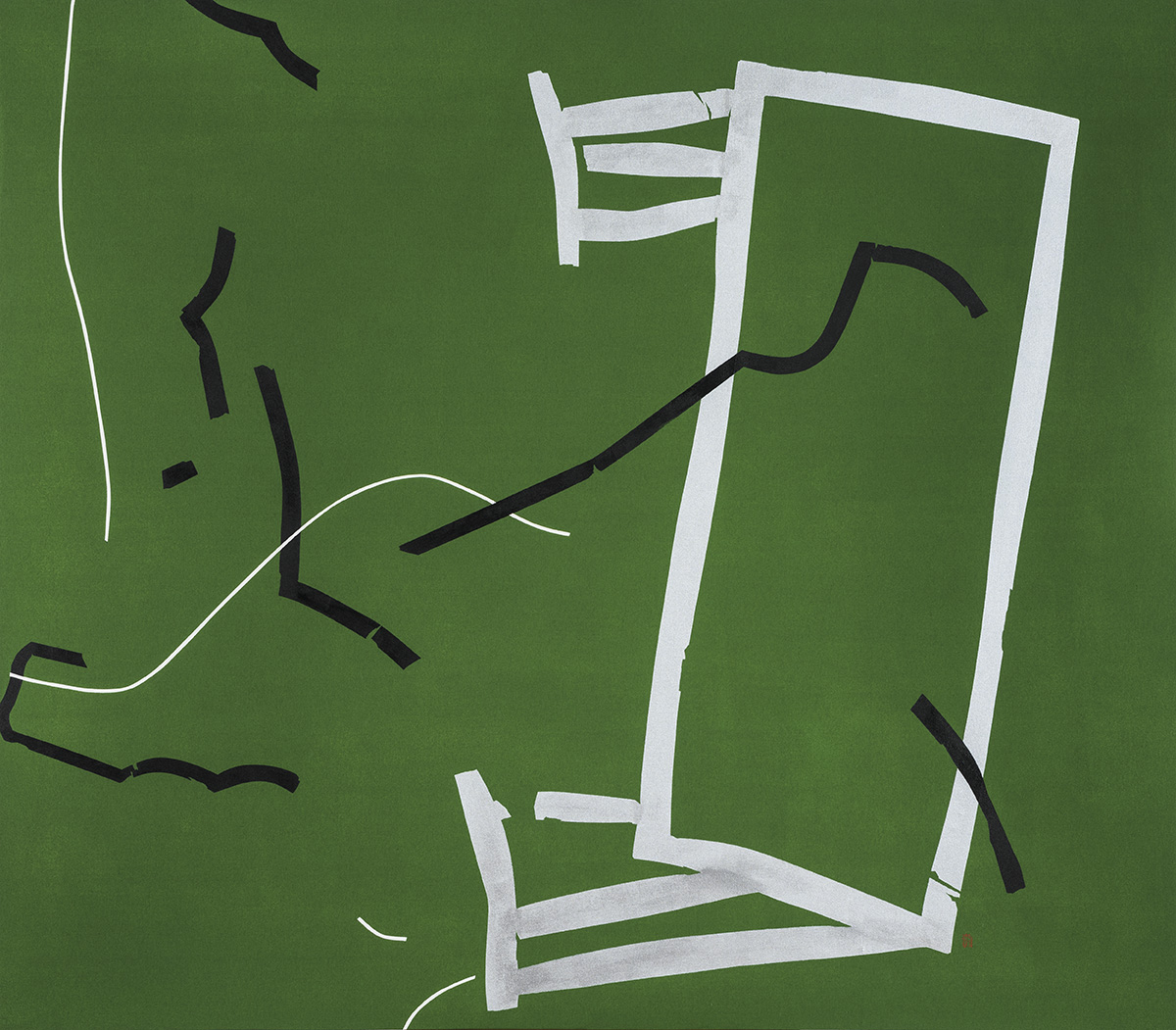

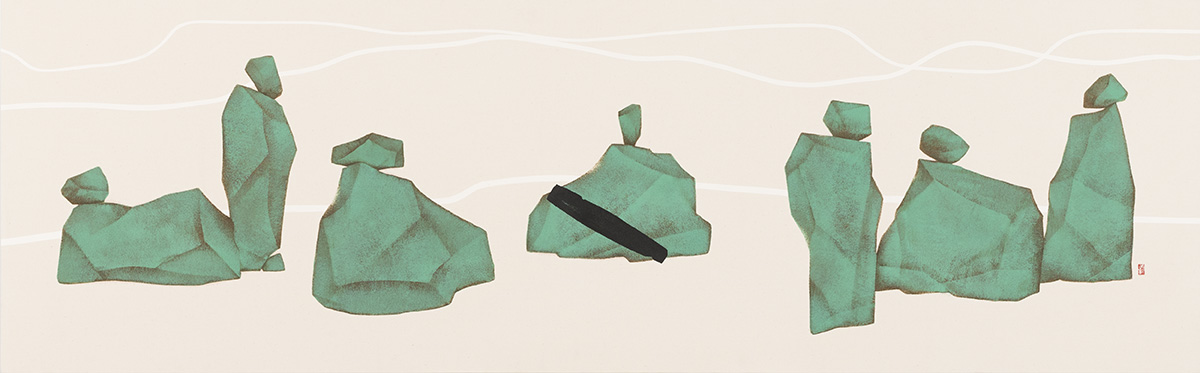

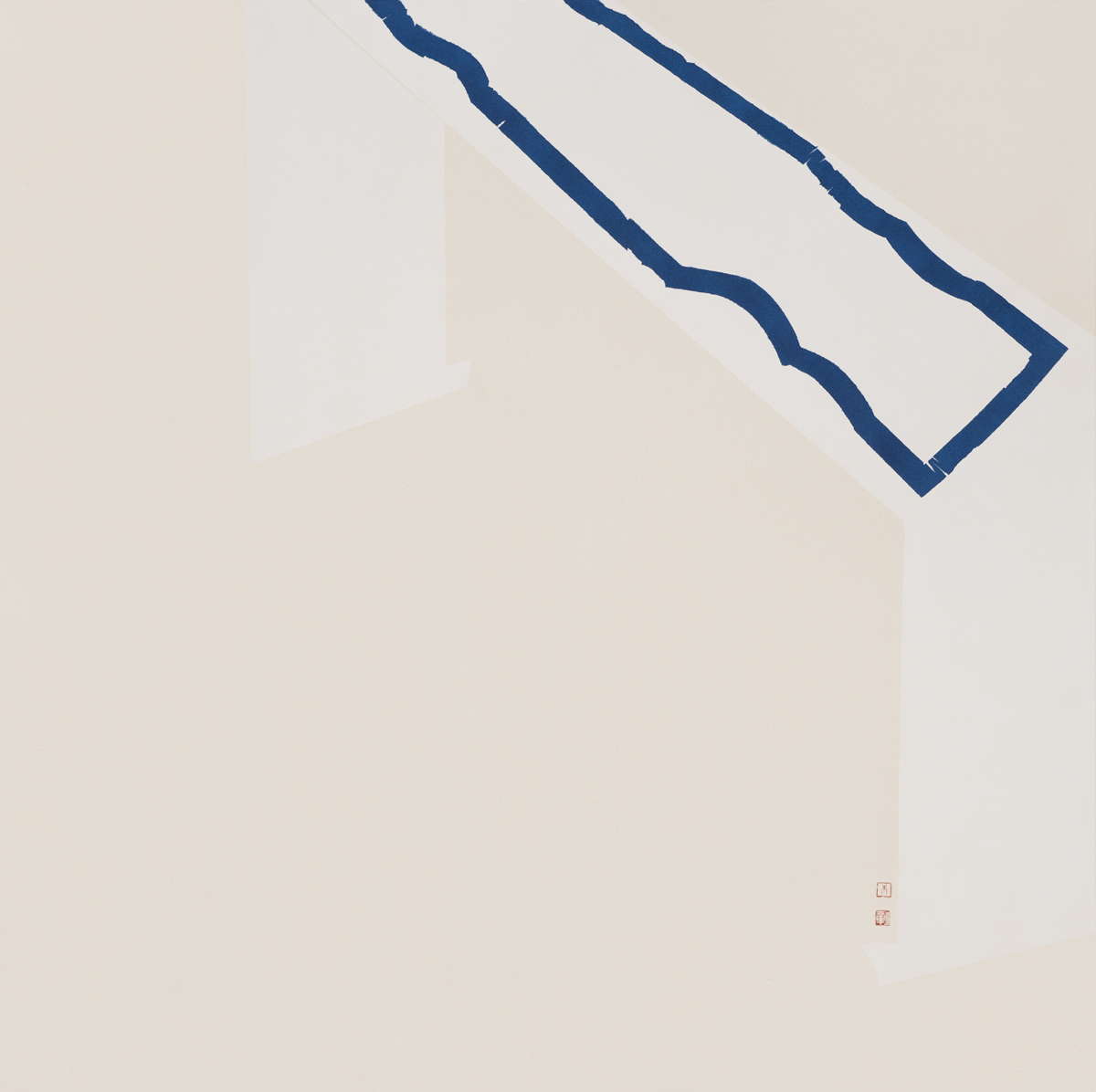

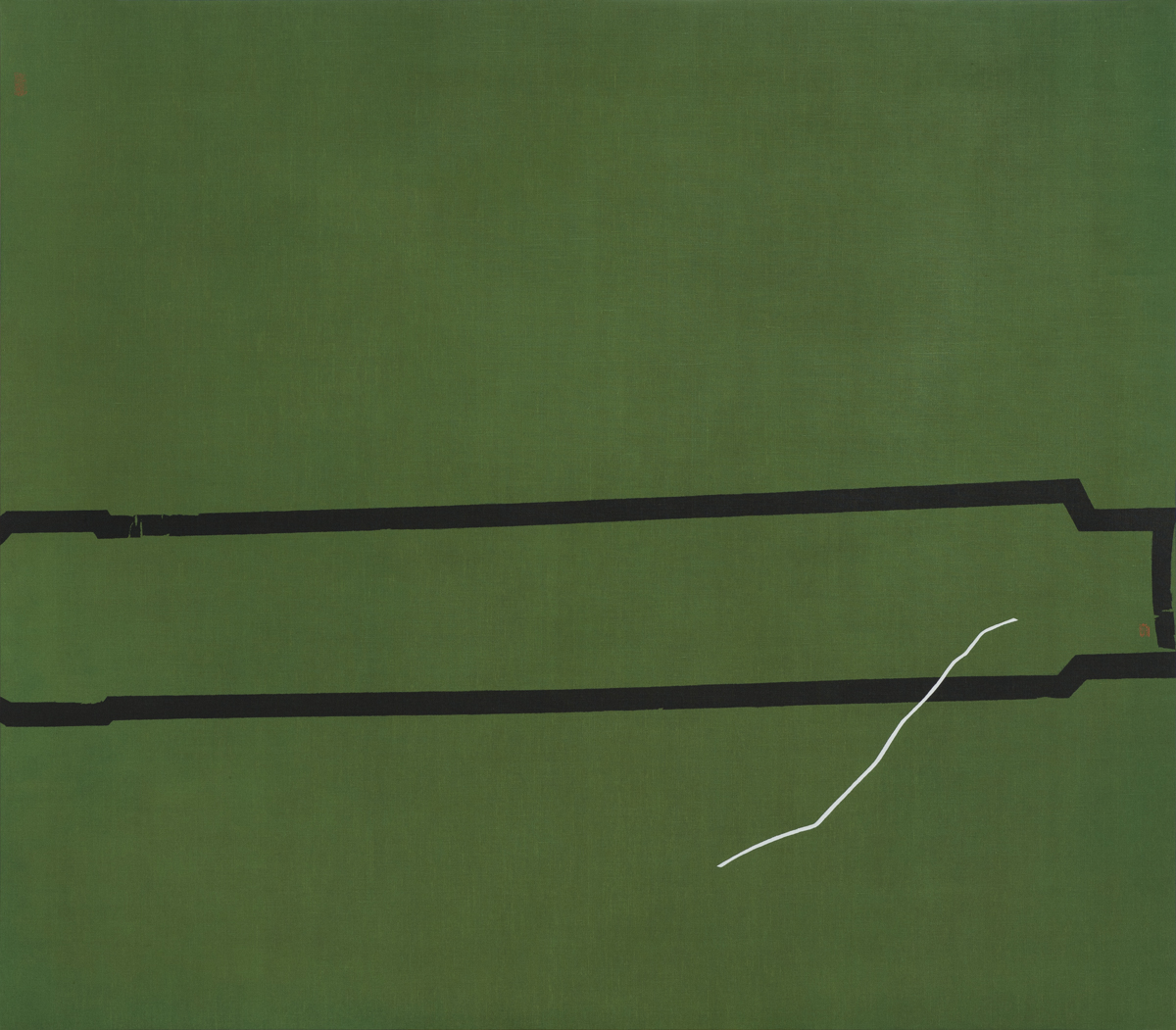

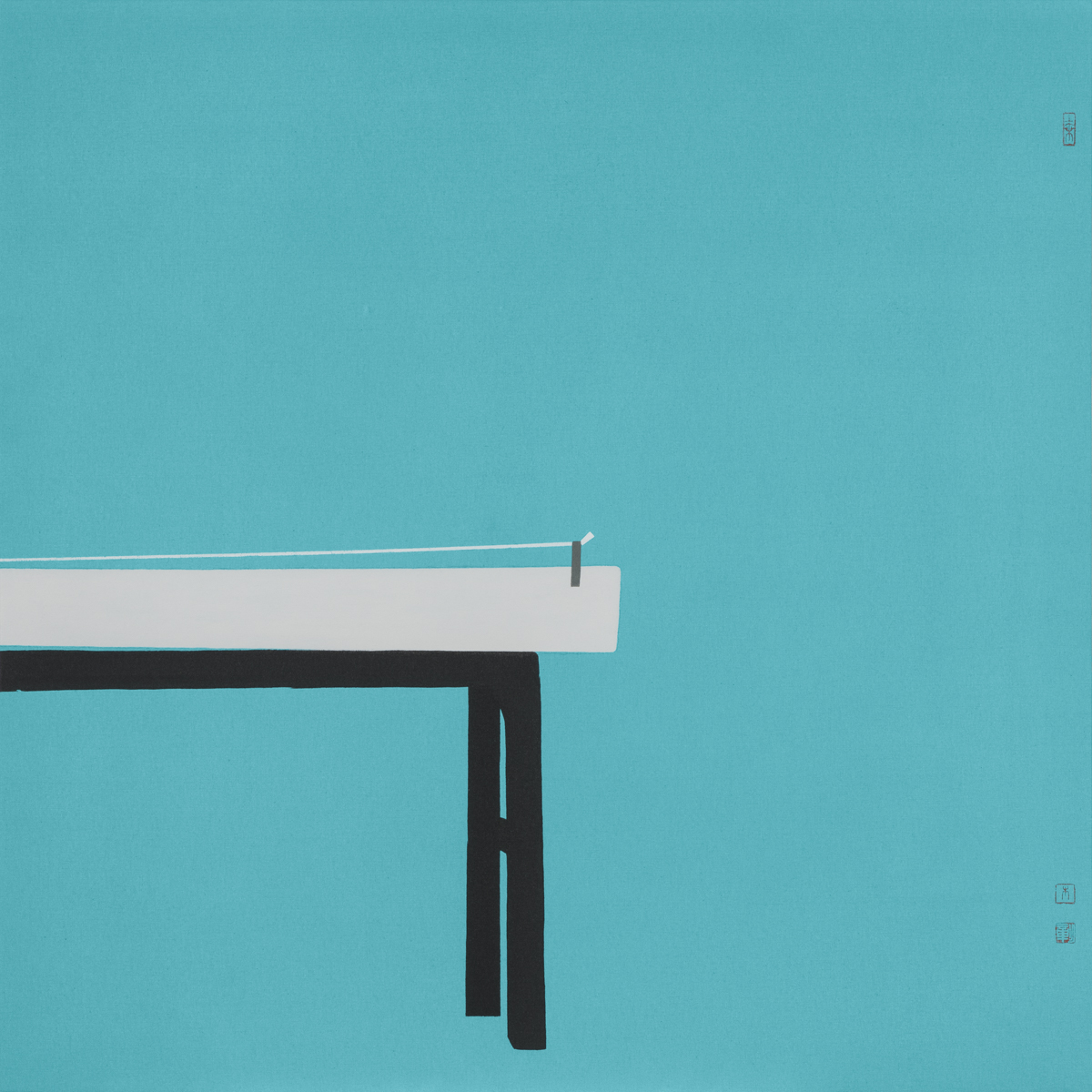

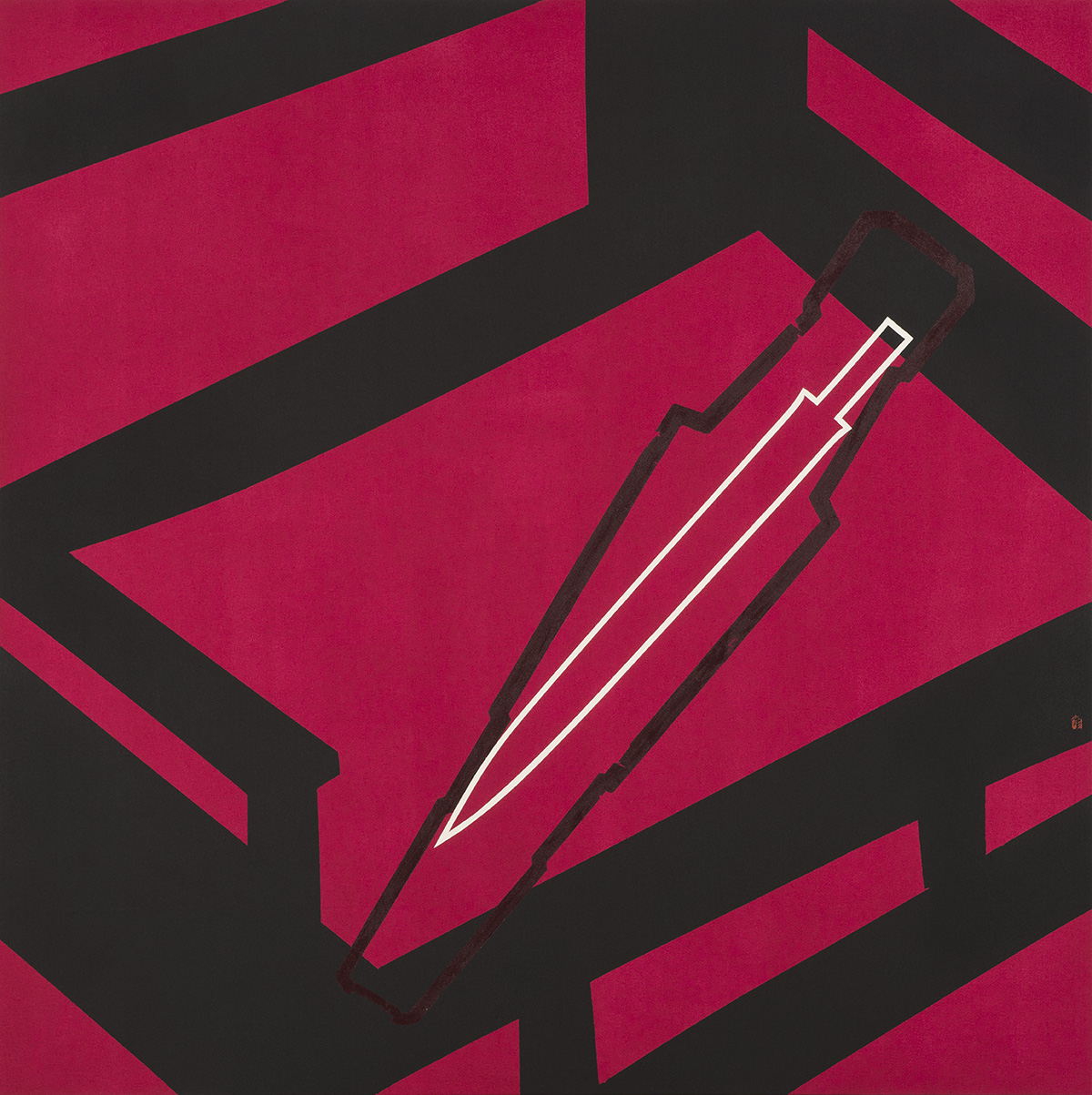

GUQIN古琴

140 x 140 cm

Acrylic and pigment on canvas

2018

GUQIN古琴

Throughout history, in ink and wash paintings the guqin has always been present together with human figures and the natural world, either with someone playing the instrument, or a gentlewoman or pageboy carrying one.

However, with the guqin as the focus, what Tay wants to express is a kind of absence or a metaphor – the artist’s way of re-embracing a traditional image across the gap of time and space and through many cultural filtrations and processing.

As a symbol of absence in the artist’s life and in his heart, he is ironically compelled to place the guqin in the centre of his works, and to constantly explore its significance and the possibilities contained within it. Therefore, looking at Tay’s displaced guqin, with only the dust and a console table left as evidence of its past presence, with no accompanying human figure or scenery, maybe we can understand that under a contemporary artist’s brush, the guqin can only exist in simple, minimalist form. It is a reinterpretation of the guqin painting discourse created from the prevailing tones and basis of modern life.

~ Chow Yian Ping, “From A Distance” (excerpt) in From A Distance exhibition catalogue, 2016

古琴在历代水墨画中亦总与人物及山水自然同在,被弹奏或由仕女书僮随身携带。

然而,聚焦古琴,郑木彰要说的却是一种缺憾。隔着历史时间、国度空间以及受到文化的渗透与漂洗以后,一个新加坡艺术家重新拥抱这种传统形象的方式。

它作为一个画家生活中与心灵上缺乏的东西,反而促使他将这个符号摆到作品的中间,不断的去挖掘其中的含义与可能性。

因此,看郑木彰中空的古琴、仅剩尘埃为证的古琴、仅有桌案没有人物及山水的古琴,我们或许可以理解为——当代艺术家笔下的古琴,也必须以这样的极简形象存在。那是一个以现代人的生活为基调,创作出来的对古琴绘画语言的重新诠释。

~周雁冰,《隔帘看月• 隔水看花》画册序文, 2016年

_九霄环佩_伏羲式_Fuxi Style_Acrylic and pigment on canvas_140 x 140 cm_2018 copy.jpg)